Chris Wiley on Mark Armijo McKnight

Death comes for us all. We don’t love to be reminded of it, of course. The memento mori, a humbling mainstay of pre-modern visual culture, has fallen out of fashion, muscled out of the way by the hopes that we might cheat the reaper with a battery of pills and potions, or be raptured into a digital pleroma by the eggheads out in Palo Alto.

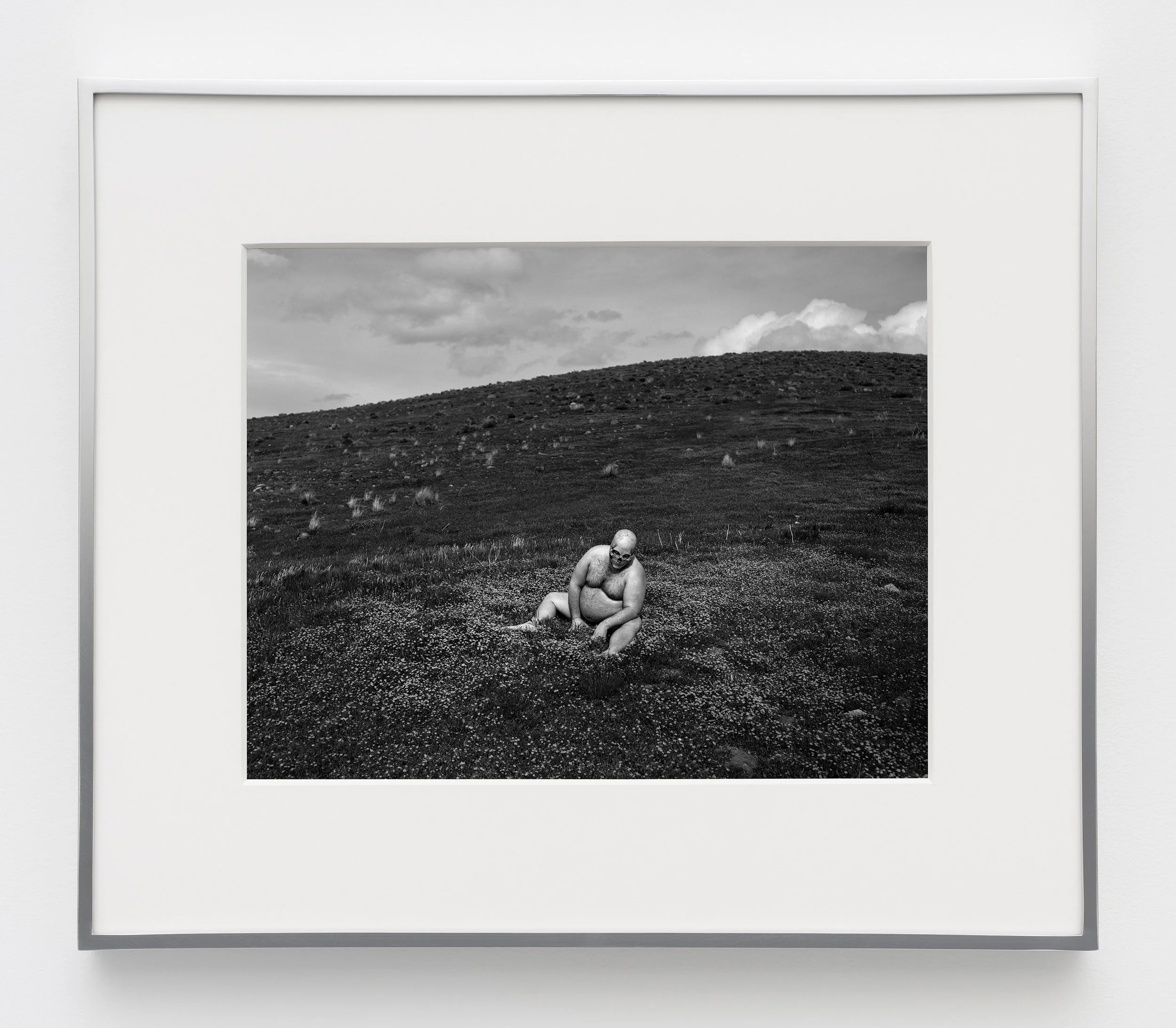

Mark Armijo McKnight’s new pictures, collected in two overlapping exhibitions in the gallery’s spaces in Los Angeles and Brussels, re-animate the memento mori, with a characteristically erotic twist. In these works, nude figures lay in the landscape, or trudge across its trackless expanses, sporting eerie skull masks. This makes for a discomfiting study in contrasts. Are these figures, with their menacing, rictus grins and comely bodies, alive or dead? Do they lounge in luxurious repose, like morbid odalisques, or have their bodies simply been scattered, like trash, and left for the elements to take them?

These ambiguities are not meant to be resolved. Nothing is ever simple. Life and death seem to have a clean, binary relationship—the switch is on, the switch is off—but that’s not always how things feel. It may not even be how things “really” are. Armijo-McKnight told me that he thinks about these pictures in relation to the Western European tradition, which is how I’ve been framing them so far, but also in connection to celebrations of the Día de Muertos, which is in keeping with his mother’s Nuevomexicano heritage. In this tradition, the dead are never fully departed.

It is not irrelevant that all the people who posed for these photographs are queer, as Armijo-McKnight is himself. During the world’s recent plague years, the governmental mismanagement of public health ominously rhymed with the AIDS crisis, stirring up old ghosts. For some these ghosts never left. I have met some of the walking dead, shattered by the stress and loss they endured decades ago.

In the Los Angeles exhibition, works featuring figures are accompanied by a pair of bleak and blasted landscapes. You get the sense, here, that the death that Armijo-McKnight is pointing to might not just be our own, but the death of our planet as well, a victim of our insouciant insistence that we can just keep running roughshod over it, without consequence. A picture in this show, of a corpulent figure snuggled into a plush field of wildflowers, appears to be a kind of farewell.

In the Brussels show, Armijo-McKnight’s pictures are accompanied by an etching by James Ensor, the famed Belgian painter of the macabre and carnivalesque. Ensor’s mature works, like these by Armijo-McKnight, are marked by the conspicuous presence of masks and skulls. These motifs found their way into his paintings by way of the gift shop run by his mother, which sold masks for his hometown of Ostend’s annual carnival.

The introduction, through parallelism, of the idea of the carnivalesque into Armijo-McKnight’s seemingly somber new work lends it a subtle air of optimism. Traditionally, carnival was a kind of final bacchanal, a period of indulgence before the abstinence of Lent. (In the context of McKnight’s death imagery it’s interesting to note that a folk etymology of the term “carnival”, derived from the latin “carne” (meat, flesh) and “vale” (to bid farewell), characterizes the celebration as a “farewell to the flesh”.) But, according to the influential analysis of Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin, the carnival was also a kind of revolutionary ritual, during which entrenched hierarchies were temporarily upended, and social boundaries were dissolved. Carnival masks, by extension, are connected “with the joy of change and reincarnation”, and in donning a mask one is able to reject “conformity to oneself”. Perhaps, then, we might be able to shake the weight of death in these images off. Make way for the new.

- Chris Wiley

Published on the occasion of Posthume, Paul Soto (Los Angeles) and Posthume: Mark McKnight with James Ensor, La Maison de Rendez-Vous (Brussels), Summer, 2023.